On 25 April 2025, the High People’s Court in Ho Chi Minh City upheld the first-instance court’s ruling in the trade mark dispute between Binh Minh Plastic JSC (Plaintiff or Binh Minh) and Binh Minh Viet Plastic JSC (Defendant or Binh Minh Viet) over the use of the mark “BÌNH MINH” for plastic pipes. This decision sparked significant controversy within the IP community.

This article discusses the Court’s controversial ruling and practical lessons for brand owners. Our analysis is based on publicly available information and media reports. As the official judgment has not yet been published, we await its release for a detailed examination of the Court’s reasoning.

Summary of the Dispute[1]

Plaintiff has used its registered trade marks “BÌNH MINH” and “NHỰA BÌNH MINH” (“BINH MINH PLASTIC”) for PVC pipes, water valves, and related goods since its establishment in 1977. The Plaintiff is also well reputed in the industry in Vietnam, having about 43% of the market share in the South of Vietnam, and 28% nationwide (according to VNR500).[2] In 2023, it discovered that Binh Minh Viet was using signs such as “BÌNH MINH VIỆT” and “NHỰA BÌNH MINH VIỆT” (“BINH MINH VIET PLASTIC”) on the same products. “BÌNH MINH” means “sunrise” in Vietnamese, while “VIỆT” refers to Vietnam.

As the Defendant’s signs replicate the plaintiff’s marks almost entirely, adding only the word “VIỆT”, Plaintiff filed a lawsuit, arguing that “BÌNH MINH” was the dominant and confusing element in the Defendant’s branding. It submitted four expert opinions from the Vietnam Intellectual Property Research Institute (VIPRI) confirming infringement, and an administrative penalty issued by a local Department of Market Surveillance against a Binh Minh Viet distributor.

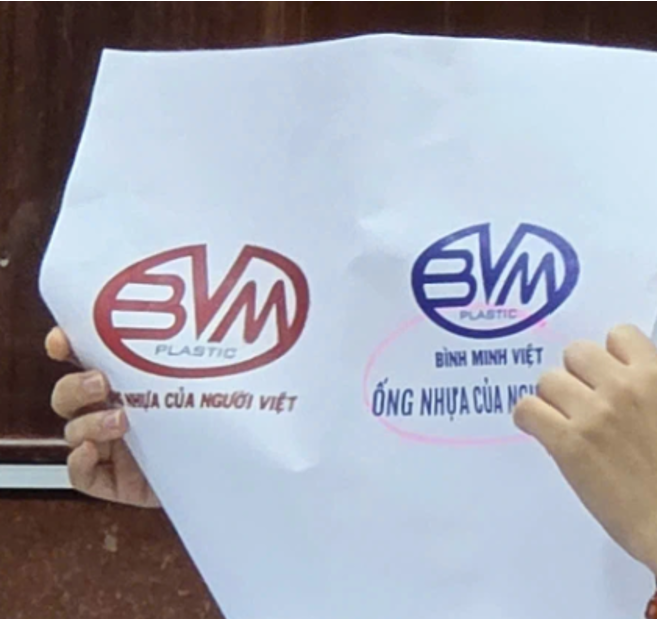

The Ho Chi Minh City People’s Court rejected the claims, finding the expert conclusions and penalty were merely referential and not conclusive. It held that the parties' logos, fonts, and layouts differed enough to avoid consumer confusion. Both parties appealed.

Defendant’s logos shown in the hearing (Source: Thanh Nien newspaper)

On appeal, Plaintiff submitted two notarised records of consumer confusion and requested a re-examination. Although the People’s Procuracy supported the appeal, the appellate court upheld the first-instance court’s decision, again rejecting the expert findings and ruling there was no likelihood of confusion.

The appellate judgment takes immediate effect but may be challenged under cassation by the Chief Justice of the Supreme People’s Court or the Chairperson of the Supreme People’s Procuracy.

Judicial Inconsistency and Systemic Gaps

The Court’s decision to disregard expert conclusions and the administrative penalty raised debates in legal circles.

The Plaintiff seemed to have all boxes ticked for a classic trade mark infringement case:

However, these were rejected by the Court, as it focused on the superficial differences in fonts, addresses, and slogans. In practice, fonts are not always sufficiently distinguishable to the average consumer, and addresses or slogans are not key factors recognised by buyers when selecting goods, especially among non-specialist consumers.

The Court relied solely on its own comparison of the signs, a move that—given the lack of a specialised IP court or trained IP judges—appears questionable and out of step. Its ruling also conflicts with relevant administrative decisions. On 8 March 2024, the Ministry of Science and Technology concluded that Binh Minh Viet’s use of “NHỰA BÌNH MINH” in its name and signage infringed Plaintiff’s registered “ỐNG NHỰA BÌNH MINH” mark. Subsequently, the Ho Chi Minh City Business Registry ordered Binh Minh Viet to change its name.[4] The court’s contrary ruling raises questions about the enforceability of such administrative sanctions.

The case also marks a break from past precedents. Vietnamese courts have usually given significant weight to expert findings from VIPRI or IP Vietnam unless procedural flaws were evident. In a comparable case, the court sided with the plaintiff against “BIA SAIGON VIETNAM” (“SAIGON VIETNAM BEER”) holding that the name caused confusion with “BIA SAIGON” (“SAIGON BEER”).[5] Yet here, with similar facts, the outcome diverged—highlighting concerns over legal certainty for IP holders.

That said, the same appellate court followed a similar reasoning in 2022, when it rejected IP Vietnam’s infringement conclusion in the “MEKONG” fish sauce case. In that case, the court also relied on its own assessment and dismissed all claims.[6]

Looking ahead, Vietnam’s new Law on the Organisation of People’s Courts, effective 1 January 2025, paves the way for specialised IP courts. These courts promise faster, more consistent decisions by judges trained in IP, a key improvement for fast-moving sectors like tech. However, full implementation may be delayed until 2026 or 2027, pending legal reforms, including updates to the Civil Procedure Code. In the meantime, IP disputes will remain with generalist courts under the current system.

Practical Implications for Brand Owners

This case underscores the high evidentiary burden plaintiffs face in IP litigation, adding complexity to brand enforcement in Vietnam. From a brand protection standpoint, the plaintiff’s case could have been stronger with:

Brand owners can consider the following preventive actions to strengthen their position in potential disputes:

Equally important is continuous monitoring—of licensing, distribution, and the market, both online and offline—to catch unauthorised use early, act quickly, and prevent brand dilution.

[1] Sources:

[2] Source: https://www.vnr500.com.vn/Thong-tin-doanh-nghiep/CONG-TY-CP-NHUA-BINH-MINH-Chart--923-2022.html

[3] Regs. No. 23374 and 490867.

[4] Source: https://congly.vn/yeu-cau-cong-ty-co-phan-nhua-binh-minh-viet-thay-doi-ten-doanh-nghiep-440795.html

[5] Source: https://thanhnien.vn/xet-xu-vu-xam-pham-quyen-so-huu-nhan-hieu-bia-saigon-185230309092745484.htm

[6] Appellate judgement No. 12/2022/KDTM-PT of the High People’s Court in Ho Chi Minh City dated 28 February 2022.

Authors: Huy Nguyen, Ly Nguyen and Uyen Doan.